How I Became a Painter In Six Self-Portraits, and You Can't Either

People ask me now whether I’m self taught. Having spent nearly a decade obtaining a fine arts degree in music costing tens of thousands of dollars, I really want to say no. I’ve purchased and copied from art books, and I was taught various basics of painting and drawing in a mandatory high school class. I’ve studied online tutorials.

I’ve been a professional artist for about 15 years. Art has not paid my rent for most of that time, but I know how to make art. I have the ability to throw hours of time and the energy you don’t really have into just practicing stuff that looks awful, and spend hundreds of dollars on materials alone to make stuff nobody will ever want. I have a vision–I know what I want to make, and why I’m doing it, and how it should look in the end. And I have the fortitude to deal with the fact that it never gets there, and there’s always something I’m not seeing, and I’ll never truly know if my work is actually “good,” and it’s probably not, and I’ll probably never make any money from it, and it may even turn me into an asshole.

But when most people ask if you’re self taught, they mean, did you pay somebody to sit down with you and explain things to you live in person, and give you personal critiques, and maybe hand you a diploma at the end of the day. In that sense, I am self-taught as a visual artist.

This is how, and why, I am self-taught, and whether I taught myself anything good.

Phase One: The Breakdown

I’ve been going to art museums for decades and I’ve always wanted to collect paintings, it just never seemed like a thing I could do, financially and otherwise. And I have dabbled in drawing on occasion for many years–there’s an unpublished cartoon graphic novel in my closet, about all the things that happened in my childhood that still piss me off, and it was great therapy to make–but I never imagined I was any good at it or that I’d want to take it seriously and really practice at it.

I work a high-pressure white collar office job. That is what occupies my time and my mind far more than anything else, and it’s what pays for my life. It’s a joy and a privilege to be an artist, but like most artists, I gotta do something to eat. And I’m really good at that other thing, it pays well and I take it seriously.

So, the pandemic started. Lockdown. My work slowed down for a week or so, but then things picked up that couldn’t wait, and suddenly I was working 16-hour days through much of March, April and May 2020 from the literal closet I’d just converted to a home office. We didn’t have childcare (we wrote checks to the daycare, and they’d promise to reopen shortly, and then they wouldn’t), and so my wife and child were running around in the background and when I was at my busiest I’d have to lock them out of the room with my office/closet in it, which room also happened to be my wife’s office and the tv room. Fun.

It was a busy time. I was indispensable at work. And we had a lot to do. So stuff like helping with cooking and childcare, exercise, appreciating and making art, all of that fell away. I sat at my desk, often 12-16 hours a day. I did my recommended exercises every morning for the joint and lower back issues I’d been having, but then I’d be all but motionless for hours.

By May, every time I stood up I had shooting pains in my right buttock and down my right leg. I started physical therapy. Too little too late: in June my right foot went numb. The right side of my body was in so much pain I was unable to function.

I took a leave of absence from work, because I was so heavily medicated I couldn’t work anyway. Then, surgery for a herniated spinal disc. Then recovery and rest. All in all, several weeks off of work, followed by a part-time return. Daily physical therapy, one to two hours of exercise at home and bi-weekly in-person visits–double masked, of course.

(By the way, in case you didn’t need non-covid related medical care in 2020—it sucked more than usual. Four checkpoints before you could see a doctor. Twelve week wait for non-emergency appointments. When I went to the emergency room for the first time after I lost feeling in my foot, they gave me opioids and left me alone for three hours (probably not a covid thing - there’s a spectrum of “emergencies” and if your heart is still beating you get less attention). Although insurance would cover my increasing opioid dosage for eight weeks while I waited for surgery, it objected to the emergency surgery recommended by my doctors and refused to pay for months after, sending me a bill for tens of thousands of dollars and backing down only with a threatened lawsuit. Notwithstanding successful surgery and thousands of hours of therapy, I have permanent nerve damage in parts of my right foot as a result of the delay.)

Anyway, the surgery was a miracle.

Nothing makes you question your life decisions like pain, medical intervention, psychoactive medication, and a forced vacation.

Phase Two: The Obsession

As I recovered from surgery, I developed an obsession. Not with painting. With the music video for “Downtown” by Macklemore & Ryan Lewis.

It’s a catchy song. And it’s a good video. But what really attracted me was the eagle-head motorcycle chariot the guy drives. (See video, first appearance at 1:45.)

It occurred to me, watching that video from my bed, drugged out of my mind, that somebody had to design and build that chariot. Like, it wasn’t just lying around, right? Somebody heard the song “Downtown,” which is a song mostly about mopeds and does not reference any eagle-headed chariots, and decided that an eagle-head chariot drawn by four motorcycles was what that video needed. And that person was paid presumably good money to design and build the chariot. It was that person’s job.

Looking back I think I had two specific takeaways from this. First, memories exploded back into my consciousness of the time in my teens and twenties where being an artist, solely and professionally, seemed like the only reasonable outcome for my life. Sure, things had taken a turn, and my intellect turned out to be more flexible than previously imagined. But I had also forced myself to forget that being an artist was also a job, that a normal and relatable person could have, and it wasn’t crazy, and in fact I kind of used to have that job. What happened to that guy? (Typical mid-life crisis stuff.)

Second, I wanted to drive that chariot. And be seen driving that chariot. A second epiphany exploded in my brain: that art tells us how to see ourselves. Shows us how we want to see ourselves. Helps us explore who we are, and answer questions about where that guy went.

In other words, the chariot from the Downtown video reminded me, during a dark night of my soul, of what questions I should be asking, and also how to answer them.

I did not realize at the time that this was happening. I probably watched the video seventy times. I’m not a teenager. I get that that behavior is normal for teenagers. It’s not normal for thirty-something professionals.

As luck would have it, the art designer responsible for the chariot had made a blog post about it. So not only could I read about that process, I even exchanged some emails with the guy. He was friendly in a why-are-we-talking kind of way.

I think I had the vague idea, at the time, that if the chariot were sitting around in somebody’s way I could offer to buy it. Not that I had anywhere to put it, or anyone to show it to. But I supposed I might have the money.

I did not. And it wasn’t for sale. But as it happened, this whole escapade dovetailed with my tenth wedding anniversary.

Now, we had been planning an anniversary party. Kind of a big one! I had accidentally purchased the services of a rock band (classic church auction newbie mistake), and we were going to invite work friends and really blow it out. But this was now early-pandemic-getting-to-mid-pandemic and that wasn’t going to happen.

THE WEDDING PORTRAIT

Instead, I hired a photographer to take pictures of my family at the site in Maine where we got married. This took some doing, because we got married in a field and the owners of the field had moved, so I had to blind mail the new owners and beg access, and it was a whole thing but in the end they were happy enough to let us on the property again and it worked out. But in the meantime, considering a backup plan, I decided that the cool thing to do would be to commission a painting of the family.

I’m not sure where this idea came from, other than just dicking around on the internet. I had the brilliant idea of having someone paint my face onto a famous portrait of George Washington or something–it was probably Alexander Hamilton, Hamilton had just come out on Disney Plus and we were briefly obsessed along with everyone else–and I quickly learned that this was not an original idea. There are hundreds if not thousands of people on the internet very happy to paint your face onto a famous painting of a statesman or an admiral or a pretty lady or whatever. At many different price points.

Now, what I really wanted was a pastiche family portrait, with myself as a George Washington-Gilbert Stuart type and my wife and daughter as John Singer Sargent-esque late 19th century aristocrats. Again, this was not really beyond the pale. It was not hard to find a market for this either.

Fortunately I guess for my psyche, I came up with a specific concept (a specific blend of famous paintings) that nobody else had done before. Unfortunately for my psyche, that meant I needed an actual talented artist to understand the concept and pull it off, not one of the unaccredited randos who will accept money to do this stuff on the internet. Of which there are clearly many.

So I paid a guy nearly a thousand dollars to execute my custom painting. This was on top of the $500 for a photographer in Maine, because by that time that plan had also worked out. But you know what, a photograph is not a painting. And I didn’t love the way I appeared in the photos. I had gained a bunch of weight in recent years and the pandemic and health issues didn’t help. I looked, and felt, old and fat and tired. I wanted somebody to paint me looking handsome. So I found a very talented professional artist.

The painting turned out pretty well. It wasn’t a great likeness, but I had been unwilling to spend much on a large painting, and I hadn’t sent great reference photos. It was more that the concept had been executed to perfection. The painting showed me how I wanted to see myself, mostly. That’s what I wanted, mostly.

Later, I paid an unaccredited rando another $500 to take that same painting and do a really big version of it–48 by 60 inches, wall-size. This guy was in Bulgaria and I found him on Etsy. I guess Bulgaria is a cheap place. But this version of the same painting was scary and awful looking. (I now keep it in a closet and bring it out for laughs at parties–always a hit.) But for the talented, accredited first artist to do a version of the same painting at that size would’ve been about $6,000.

I wasn’t ready to spend that much on art. Yet. And also, the one concept I’d really enjoyed–the combo of Stuart and Sargent–was starting to seem to me a bit hokey. I realized that a piece of art that was that level of jokey and referential really didn’t captivate me. What I wanted was a real piece of art. Referential was fine, but I wanted something that could stand on its own.

I had spent an amount on paintings and photos that was already embarrassing. I had taken a pay cut during the pandemic and we had been paying for daycare we weren’t receiving, and in the fall of 2020 we began paying for substitute childcare, someone to sit and watch my daughter while she attended pre-kindergarten via zoom. It was not a good time to blow thousands of dollars commissioning paintings.

And yet I couldn’t stop thinking about paintings. I bought a book of Sargent paintings, got a book on Velazquez from the library, took trips to the museum. Whatever it was I’d hoped to capture with my custom painting, I hadn’t gotten it. I wanted a better portrait of myself, a really good one. More than that, I wanted great portraits of my family to hang all over my house. It was tearing me apart. Was I just going to have to save up for years and years, slowly buying painting after painting to decorate my house and really execute my vision?

No. Obviously, no. Whatever my financial future held, it was obviously and forever insufficient to acquire all the art I wanted. That was a bottomless pit that would require me to dive much deeper into my career than I could ever stomach, and it might take 20-30 years. Though it would take a few months to accept it, because I’ve been down this road and I do understand it take years, maybe decades to master a craft like this—even so…I understood on some level that if I were really serious about this art bullshit, I was going to have to do it myself.

Phase Three: Baby Steps

From September to November of 2020 I watched a lot of youtube tutorials. Not that I’d made any decisions about my artistic future, more that I would get high (mandatory, back pain) and watch people paint faces, or restore old paintings. And whether I was high or not, it seemed super cool.

I don’t know when I made the decision to try it myself. It was pretty gradual. I was spending a lot of time with my daughter (still stuck in the house almost all the time) and her favorite activity was to dictate books to me. She’d draw the pictures and tell me the story to write down, and I’d write it down and she’d yell at me for doing it wrong. We have hundreds of these books. At some point I started doodling some pictures of my own alongside hers, which probably also pissed her off.

Finally at Thanksgiving, at my parents’ house, I was getting bored and frustrated and needed a distraction from thoughts of climate change. My brother was asleep in a chair and my daughter had spilled a bucket of crayons across the floor to make drawings of her own, and I decided to draw my brother.

I drew him. And it came out ok. It was a recognizable likeness. My parents being my parents and endlessly proud of me, they were very impressed. And I guess that was all I needed.

(Cue eyeroll from my wife.)

Phase Four: Canvas

By the time we returned to Boston from Thanksgiving, I knew I needed to try a real art project. I was pleased to find that Michael’s sold cheap art supplies–like, really cheap. I knew they weren’t high quality. But I wanted to see what I could do. I wanted a self-portrait in oil on canvas.

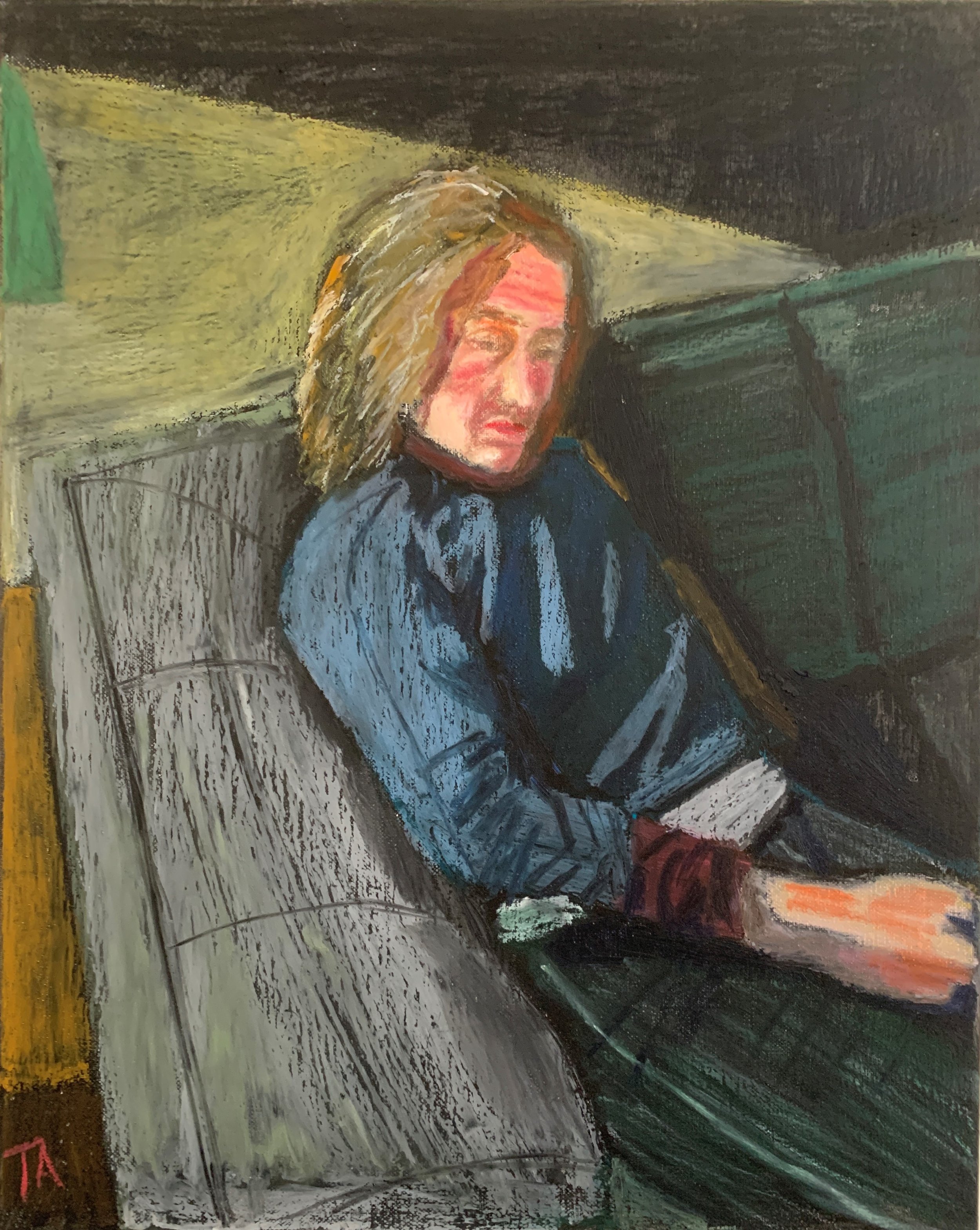

I chose an 18x24” student grade white canvas. I had already selected oil pastel as a medium–I wanted something that could get an oil paint-like gloss that wouldn’t require me to mess with paint thinner and brushes. So I bought the really cheap “Artist’s Loft” brand oil pastels that Michael’s sells. Total initial investment of under $20.

In this first effort I didn’t use any kind of formal drawing technique. I eyeballed it. I ended up with a weirdly angry nose that looks nothing like my nose. Way too much blue in the eye sockets. I look fucking furious. I actually like the shirt though.

This first self-portrait took me over 20 hours. I agonized over it. A large part of that was the cheap materials–it was a pre-primed canvas, but I later learned to triple prime, and the Artist Loft oil pastels are hard as shit, they don’t spread pigment easily. I mean, oil pastel on canvas is a bit insane to begin with, it’s not a good surface for oil pastel. So I really had to fight to get the pigment on. And I think that frustration and that physical energy come through in this painting. It has a certain cubist energy to it.

After this, I drew another portrait or two, experimenting with grid drawing methods and different materials. I did a portrait of my sister-in-law in dry pastel, realizing in the process that both (1) pastel drawing and (2) the female face is pretty damn unforgiving. There are not many lines, and so you have to get all of them exactly right or the face just looks generic. (Have you noticed the abundance of generic hot girl paintings in art? Hmm.) So you can’t just rub and smush and push pigment around, you have to actually know what you’re doing and lay it down on the first try.

Today, I’m not that pleased with my other earliest efforts. I also wasted a bunch of money having some of these early efforts framed, because I thought that’s what you had to do. I mean, I’d put dozens of hours into these things. They were fucking special. What was I going to do, chuck them in the basement? (Narrator: yes.)

I gave them to my parents. My parents were very proud. Only later did I start to feel bad about that.

Phase Five: Experimentation

Research was telling me that it shouldn’t be physically difficult just to get paint on canvas. I needed to make a few corrections.

First, I had to learn about canvas. I quickly learned to apply additional coats of primer so that the medium wouldn’t just sink in. For months I toiled with acrylic primer, only later to discover classic oil primers that gave the canvas an impermeable shiny bounce. Similarly, it took months and much time and money to find the right grade of canvas for what I wanted–the cheap student canvases were low-density cotton, and the texture of the cotton weave would be visible no matter the density of paint applied.

Second, I had to learn about the medium. This was still the pandemic and it was very cold out, and my “studio” was in my family’s dining room. Any kind of liquid paint was really out of the question, and I had to keep my use of solvents to a minimum. So, but for a few further experiments in decent weather, when I could paint outdoors, I stuck with oil pastels.

Oil pastel companies advertise that you can paint your work onto the canvas by mixing with solvent. And there is a company that makes water soluble oil pastels, which hypothetically function the same way.

My experiments in early 2021 showed me that this wasn’t entirely true. Yes, you could apply and manipulate oil pastel with brushes. But you don’t brush the paint on, you brush it off. You can’t mix the paint on a palette, you have to draw it onto the canvas with the crayon itself and then push it around with the brush, and the brush would always remove some pigment in the process. The amount of solvent on the brush and the type of stroke would determine how much pigment was moved and where it ended up. Any attempt to blend would result in a muddy, disgusting mess, so you’d have to be really happy with the color in the crayon, and apply it directly onto bare canvas or a very dry underpainting.

The brushwork was good for creating backgrounds, large washes of color. But it was frustrating as all hell to try to draw with brushed oil pastel.

Third, I had to settle on a brand of oil pastel. The water solubles were nice, but they came in a set of 24 colors and didn’t blend particularly well. The palette was too limiting (and not even designed for portraiture). I splurged on a 24-color starter pack of Sennelier oil pastels. Sennelier is one of the premium brands, supposedly designed with the input of Picasso himself, though I could never confirm which, if any, of his works were created with them. At any rate, Sennelier is known for vibrant colors, spreading like butter, and blending well.

That was more or less true. And the Sennelier also responded well to brushing, although brushing dropped out of favor as I discovered more effective techniques.

If you’re reading carefully and know your art supplies, you might be thinking “wow, big surprise. He toyed around and discovered he likes triple-primed fine linen canvas and Sennelier oil pastels, all the expensive primo shit that everybody else likes too.”

Yes. A set of Artist’s Loft oil pastels was about $10. The full set of 120 colors of Sennelier oil pastels in regular size crayon was about $350. Today I have the full set. And a jumbo size collection of 30, for underpaintings and rough sketches. And a few replacements and backups. I have about $1,000 of Sennelier paints today. And probably another $1,000 in primed linen canvases in my basement.

But at this point, we’re still in early 2021, my art supply purchases are still in the hundreds of dollars, not thousands. I’m trying out brushing and so on. By January, I have a small number of paintings that I really like, and that I’m still fond of today.

This self portrait I did in about two hours. It’s unfinished, as are a lot of my paintings, because I often just stop once I’ve captured something important, or whatever it is I was going for. If I were to plow back into the painting and really work on the nostrils or the mouth or whatever, I’d lose it, and I’d have to fight to get it back. That’s sort of the nature of artistry, one of the things I learned outside of visual art: sometimes unfinished is just fine. With every level of finish, you have to re-work the entire piece, to re-harmonize it, otherwise you ruin the proportions and the flow.

Most of the self-portraits I’m showing here are studies—not created to be a finished work, although I’m proud of them and consider them finished for my purposes. Some of my more classically finished works are below at the end of this essay.

Each successive layer of finish takes more technique to pull off well, and I don’t have a ton of technique yet (certainly not in early 2021, with about six weeks of painting under my belt), so I’m more inclined to settle for a lower degree of finish if I’m still capturing whatever else I want. But you can’t confuse finish (or hyper-photorealism, at the highest levels of finish) with good taste. There’s a reason most people are not fans of Ingres, and there’s a reason nobody really cares about the thousands of instagram artists that can paint a portrait that’s indistinguishable from a photo. It’s just not, by itself, all that interesting, and generally you can devote way, way too much time into finishing a piece and lose whatever made the subject and the composition interesting in the first place. My time is too valuable to me to risk that.

Here, in just a couple of hours of sketching and brushwork I thought I captured my expression in a compelling and accurate way. There is a certain magic that happens when you make a few good decisions, you get the drawing and the values just right, and suddenly it’s not an exercise anymore, there’s a person staring at you. Those are my eyes.

Interlude: On Drawing, Materials, and the Class Struggle

You might ask, what about pencils, pens, watercolors, etc. Well, I do have a set of pencils, and I do some drawing in pencil for training and experimentation purposes and prepping my compositions. I’ve done some landscape sketching and live model sessions and whatnot. But that does not inspire me. I have created a small number of relatively finished pencil works, but they’re not my best and I don’t enjoy it.

I recognize that drawing is the most important skill, the heart of painting. And I put a lot of work into accurate drawings underneath my paintings, sometimes using tools like grids or projectors to assist. But I’m not a great draftsman, and I don’t think that’s going to change. In part it’s just inexperience. I may also have some form of aphantasia–I can’t generally envision where lines should go. So I generally draw and paint by creating splotches of value (lights and darks) and then pushing them around until they start to look right, and then I sharpen the edges.

The traditional art school curriculum–the atelier system of realist art–would be drawing, drawing, drawing, just pencils for maybe a couple of years before you touch a paintbrush. But I have a limited amount of free time for art. I’m not going to take a few years to do only the tedious bullshit. And I’m not Paul Gauguin, I’m not abandoning my family and choosing poverty to live the real life of an artist. I want to paint, so that’s what I’m doing.

I know that many artists would read the paragraphs above and bug out. (I have spoken to one artist who bugged out.) I know it’s frustrating for someone who’s struggling to see someone screw around with Sennelier pastels and fine linen canvases, the same way I used to hate when you’d go to a friend’s house and there’d be a Gibson L-5 on the wall because his lawyer dad was having a midlife crisis and that was the guitar he’d always wanted and could never afford in his cool musician days. Well, I am that lawyer dad. I can easily afford better materials than some artists who have sacrificed a heck of a lot for their pedigree, their craft, their credibility in the art world. All I can say is I come by it honestly. I’m not trying to re-live any glory days, and it doesn’t hang on the wall unplayed like that L-5. I’m just making art, buddy.

Phase Six: Fingerpainting

In March 2021 I made one of my most important discoveries: smudging the paint in with my fingers. This cured a number of problems inherent to painting with oil pastel on canvas.

First, the smudging dulled some of the vibrancy of the pastels. Vibrancy is great, but if you’re inspired by late 19th century portraiture, it’s not always appropriate. Neon is wrong. But even smudging a monochrome would wash out the colors just enough to pass for the Zorn palette. Smudging multiple colors together would provide an infinite palette, and something about the oils in my fingertips bonded the colors better than mere rubbing of the crayons. (For finer work, a q-tip would suffice, but the q-tip would also absorb more pigment than was really helpful.)

Second, the smudging smoothed the texture of the canvas itself. Even with finer weaves, this was always a problem.

And third, smudging could be used to create certain textures that livened up my backgrounds. It would never be the same as the slapdash blacks and browns we know and love from classic portraiture, but it was it’s own thing.

My first painting really utilizing smudging was this self-portrait. It has some drawing issues, but I was happy with the new effect. (Gave it to my parents.)

Having made this discovery and confirmed its utility on a couple other pieces, I felt confident enough to try a significantly larger work.

The context to this 30x40 inch monstrosity is that I had been selected to give a presentation to a number of colleagues about certain marketing efforts at work, and it was by design a somewhat self-aggrandizing presentation. I thought it would be hilarious to give the presentation (from my closet, via zoom) and then briefly/inadvertently toward the end of the presentation turn the camera so that people would see a giant portrait of my own face, hanging behind me while I worked. I think it’s the most time and money I’ve ever committed to a single joke. Went over ok.

This painting does come off much better in person, because the size of it (nearly double life size) makes it intimidating and absorbing. It has an interesting texture from a mixture of different techniques (you can see the brushwork in the background). And the colors are more subtle with indirect lighting. This is true to some extent of a lot of my works. Maybe I don’t take great photos, but I think converting to jpeg just isn’t great for paintings. The point is to be in its presence.

Phase Seven: Maturity

For nearly the next year, I took a step back from the self portraits. I had a number of other subjects I wanted to tackle (some involving myself as model, but not portraits per se) and I didn’t feel I needed to benchmark myself with self-portraits. I’d gotten tired of painting and drawing myself.

That boredom with the subject is reflected in this 16x20-inch self-portrait from March of 2022, entitled “This is Gonna Be Worth Money Someday!!!”

By March 2022 (about fifteen months into my odyssey) I could toss off a study like this in 3-4 hours. I hung it in my bathroom. I like hanging paintings right where they were painted, and I like paintings where the subject is staring at you kind of angrily. If you pee standing up at my house, you’re going to see me sitting on that same toilet, judging you like an angry ghost. Fun.

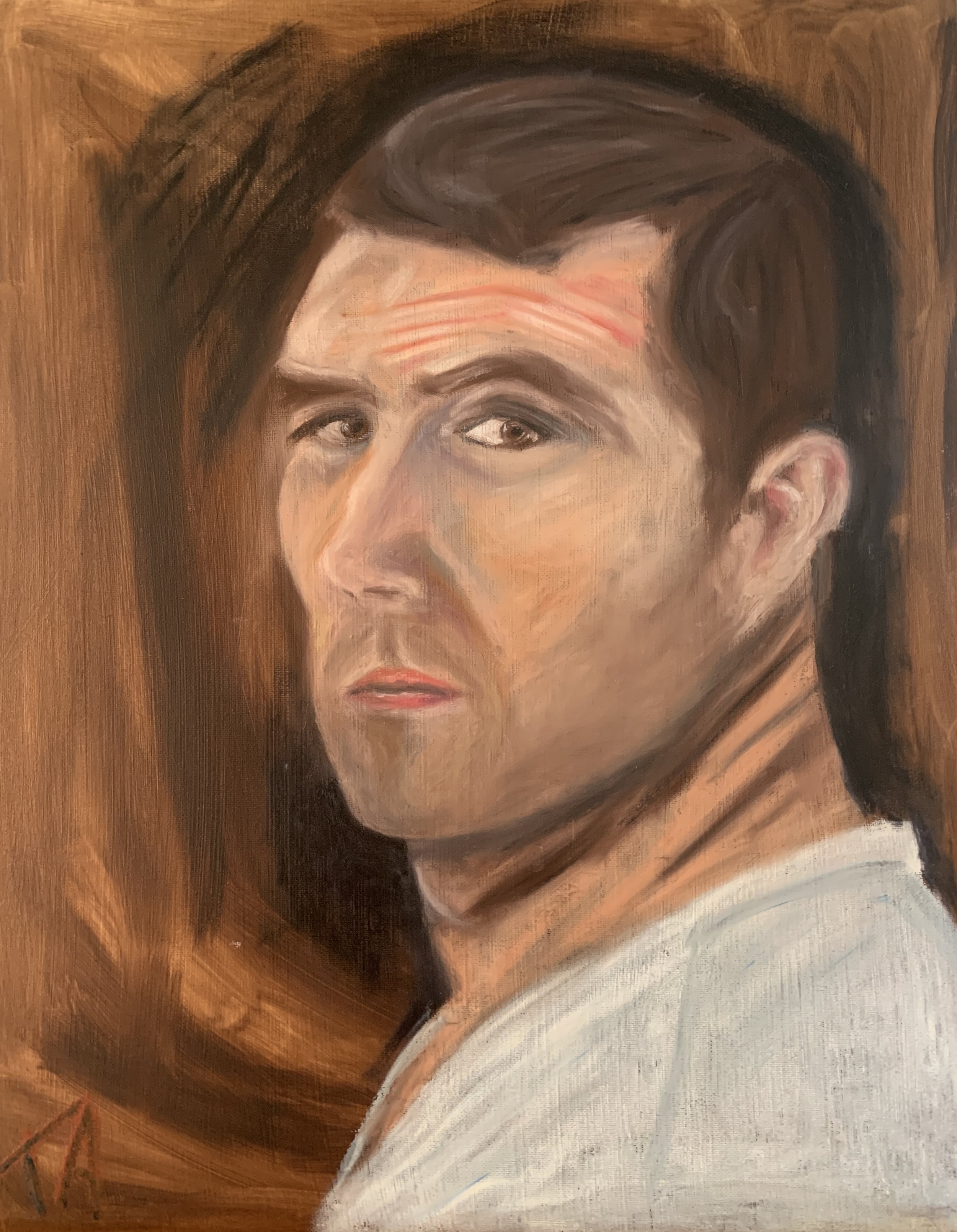

Phase Eight: Alla Prima

The one thing I hadn’t done much of to this point was alla prima. Most of my paintings were either from reference photos or at least reference-assisted. This was mostly due to my insecurity over draftsmanship, and not wanting to waste time and money, and wanting more control over my compositions. (Spending a rare free weekend day on a painting, using expensive paints and meticulously primed canvas, only to catch a drawing issue that totally compromised the composition…the absolute worst. Preparation is key.)

But in mid-2022 I started to get really into this UK reality show Portrait Artist of the Year. It’s not unlike the glory days of Great British Bake Off, in that it’s very kind, very process oriented, not particularly manipulative. It’s just talented artists painting a live model. The competition element isn’t even all that important.

For the most part, PAOTY is a four-hour timed alla prima sitting of a celebrity. At the end of four hours you’re done. Some contestants use grids, but regardless, your drawing skills need to be en pointe.

I’d been doing some live model sketching sessions and so on, and I’d done a few self-portrait sketches in pencil and crayon on paper, and finally in July 2022 I had a semi-free Saturday (I was actually on call at work, natch, but it meant I couldn’t leave the house) and I decided to give it a shot.

I cheated a bit - the day after, I corrected a few values and tightened an edge or two. But frankly I’m astounded at this result.

I can see some flaws in it, and I’ll definitely see more flaws down the road. It’s not a work of genius. It’s just a self-portrait study. But this looks to me like it could’ve been painted in the 17th, 18th or 19th century. And it definitely, unmistakeably looks like the guy in the mirror, both how I actually appear and how I’d like to be seen. I would not have guessed from painting #1, which took easily five times longer to complete, that I could ever get to this place.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I’ve applied to residencies, and I’ve received a few commissions and my work is hanging on a few walls. I’ve made the decision to refer to myself–with friends, at least–as an artist, again. Which I never felt was untrue, but during my first decade as a lawyer it didn’t seem prudent to say.

It takes a lot of courage to call yourself an artist. I feel vulnerable about it all the time. I can envision other artists reading this and judging me. I have no doubt they could do all of this stuff better and point out a thousand things I’m doing wrong. There’s always a million people on the internet who are better than you.

I’m insecure about my art all the time. I’ve had to ask my wife over and over again if it’s any good. She says she thinks so. But she has to see it all the time too. It’s too hard for either of us to tell. Also, it’s not very nice of me to keep asking.

I get compliments sometimes. I think they’re genuine. A few people I respect have really, really liked my work. But a lot of people I respect have seen it and said nothing. And I’ve been rejected from residencies. What does that mean? That they hate it and are too polite to say? That they admire it and they’re jealous of my talent? That they see it as the work of a beginner or an amateur, not real art? That they’re indifferent to this art, and most art? Who knows.

One of the things I had forgotten about being an artist, after a few years of not trying to sell art, is that never knowing. You can like your own work, and that’s great, but it’s never enough. You can even have an agent, a publisher, successful gigs, whatever, and there’s no compliment that’s the right compliment. You never know if it’s any good. And when you start making something, you definitely don’t know if it will be good, or if it will sell, or ever be appreciated. Nobody’s paying you a salary. You’re just hoping that someday someone looks at it and whatever chemicals in their brain activate and they, what? Become happy? Achieve enlightenment? Decide to give you money? Emotions aren’t truth, they can’t be predicted, no serious person would make a business out of doing this.

Being an artist is insane. It’s a fucking crazy thing to do.